The high frequency challenge – from Zenith to Seiko and beyond

14 December 2020Switzerland, Japan, Germany. They are the vertices of the Haute Horlogerie triangle that have always contended for the primacy of excellence. The rivalry between the first two has been very heated at least since the 1960s, when, before the tsunami of quartz overwhelmed industry and markets, the challenge of perfection was played on the most precise movement ever, gradually aiming to higher frequencies.

The quest for the greatest precision through the increase in vibrations ignited a challenge which, as often happens in these cases, has brought advantages to the whole sector, because it has led to some of the most important movements of the twentieth century: El Primero by Zenith and Hi-Beat by Seiko.

THE HIGH FREQUENCY CHALLANGE

Until about the middle of the last century, the calibers of most watches beat at 18,000 vibrations/hour. Gradually the race towards precision began and led to a progressive increase in vibrations, first to 21,600, then to 28,800, with the aim of reaching 36,000, the maximum achievable at the time.

Using more modern materials for the construction of hairsprings and balance wheels, in the 1950s the calibers beating at 18,000 vibrations/hour had an accuracy within 1 sec/day: improving similar performance seemed unrealistic, if at all, useless.

However, the challenge had to be played, starting with increasing the power of the balance-spring system to improve the precision with which it divides time. How? By increasing the factors that influence its power, starting from the vibration frequency.

Since the power is proportional to the third power of the frequency, doubling it from 18,000 to 36,000 vibrations/hour increases the regulation capacity by eight times, as much as the accuracy of the watch.

Moreover, by doubling the frequency, the negative influence that the imbalance of the balance-spring system has on the accuracy of the watch worn in different positions is reduced by four times. Thus, the accuracy of the timepiece increases in any position.

All these benefits pushed the brands into competition, even facing difficulties related to the materials, stressed out by the high frequency of the caliber. Not to be boring, we will mention just a couple of them: the lubrication and the escapement.

The high frequency generated important centrifugal forces that made traditional fluid lubricants unsuitable; the high speed with which the disengagement and the impulse followed one another would have been slowed down due to the filamentous oils, so a more effective dry lubrication using molybdenum disulfide powder was chosen.

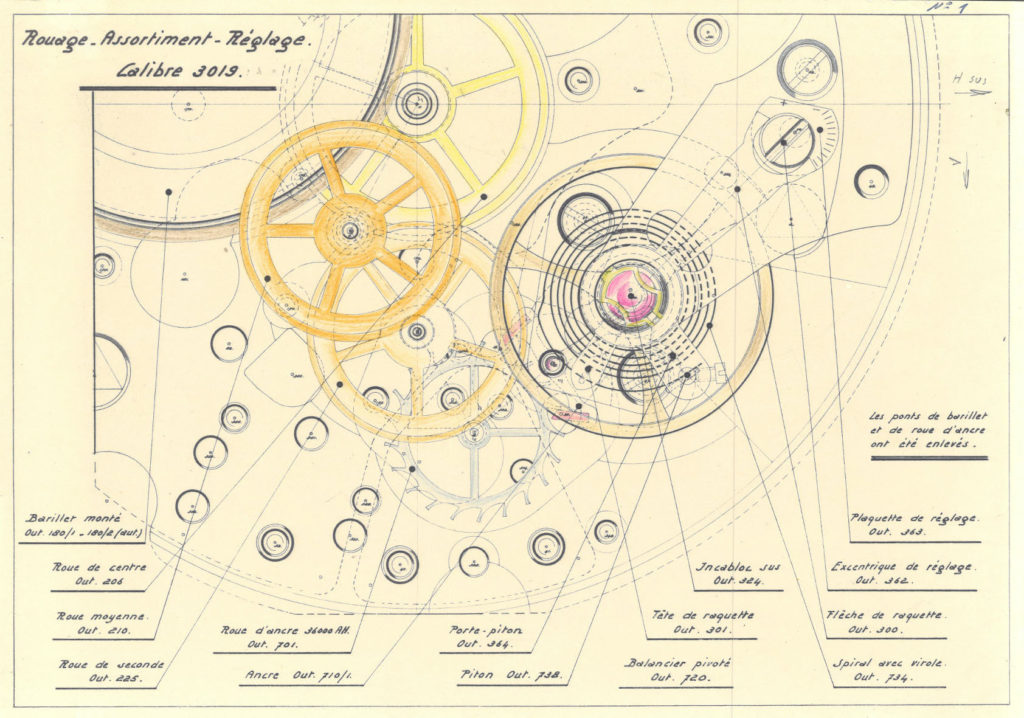

Then, the high number of vibrations led to create an escape wheel with 21 teeth instead of the usual 15, which had to be larger but lighter in order not to increase the inertia of the wheel itself. Consequently, the anchor had to be smaller and have reinforced arms to support the greater dynamic load.

Finally, the tooth’s surface laying on the anchor lever in the resting moment had to be about half that of a normal escapement: 0.07 mm instead of 0.15 mm.

THE HIGH FREQUENCY BEFORE ZENITH

One of the first manufacturers to experiment with high-frequency movements was Girard-Perregaux, which in the 1960s developed calibers such as the GP 31.7 and 32.7. From the latter came the 32A caliber that equipped the Gyromatic, presented by Girard-Perregaux in Basel in 1966; with its 36,000 vibrations, it had an impressive precision at that time. It was no coincidence that 70% of the chronometer certificates issued the following year by the Neuchâtel Observatory consisted of high-frequency Girard-Perregaux chronometers.

(Photo Credit Stetz&Co)

Girard Perregaux’s successes with high frequency prompted Longines to celebrate its centenary in 1967 with a 36,000 A/h automatic watch. Powered by the 42-hour power reserve caliber 430, the watch is known as Ultra-Chron.

THE COMING OF EL PRIMERO

Other Swiss manufacturers took these innovations as a cue, first of all Zenith and Movado, owned by the same group at the time, which had the aim of creating the first automatic chronograph with a high-frequency movement.

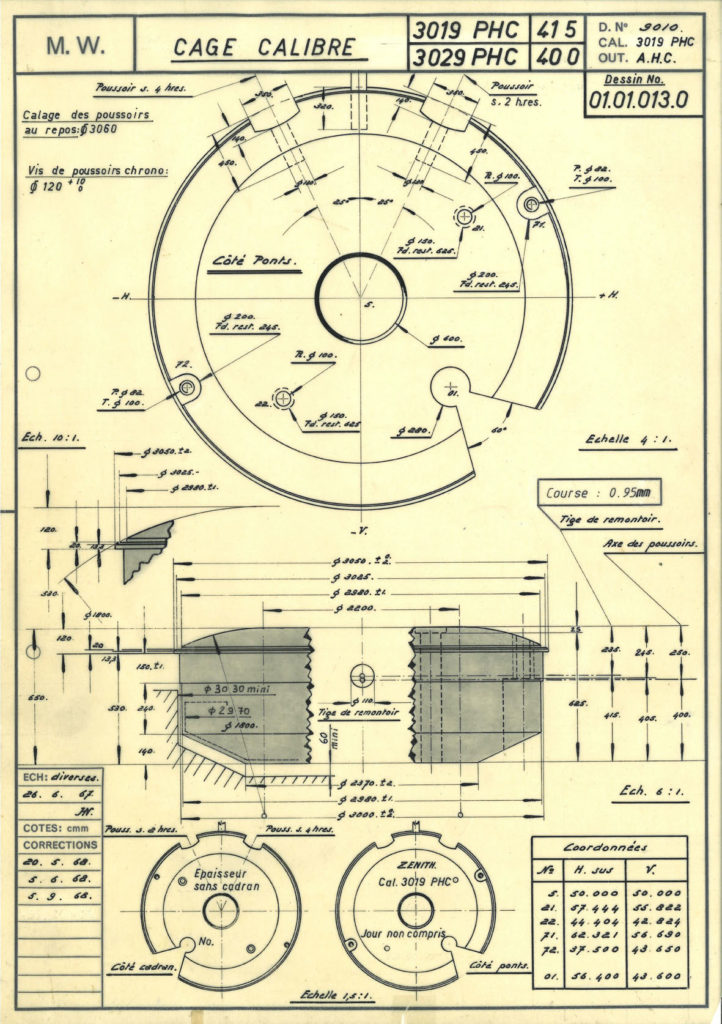

Zenith had the idea as early as in 1962, wishing to present the caliber three years later, in the centenary of the Manufacture. Work was fatally long, due to the numerous and complex requirements that the movement required.

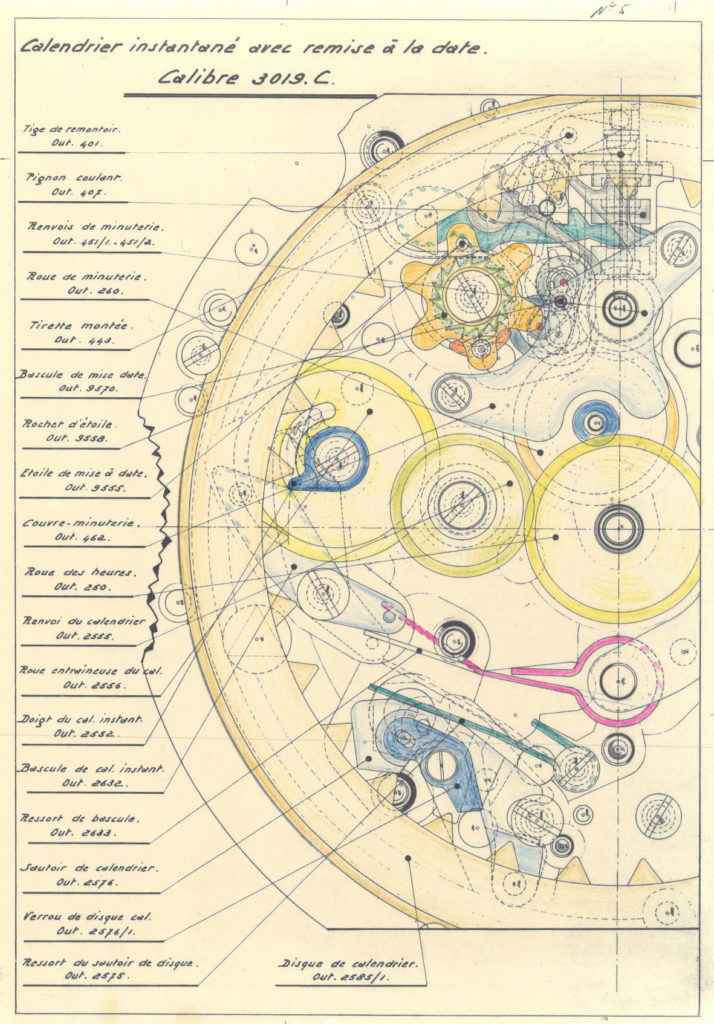

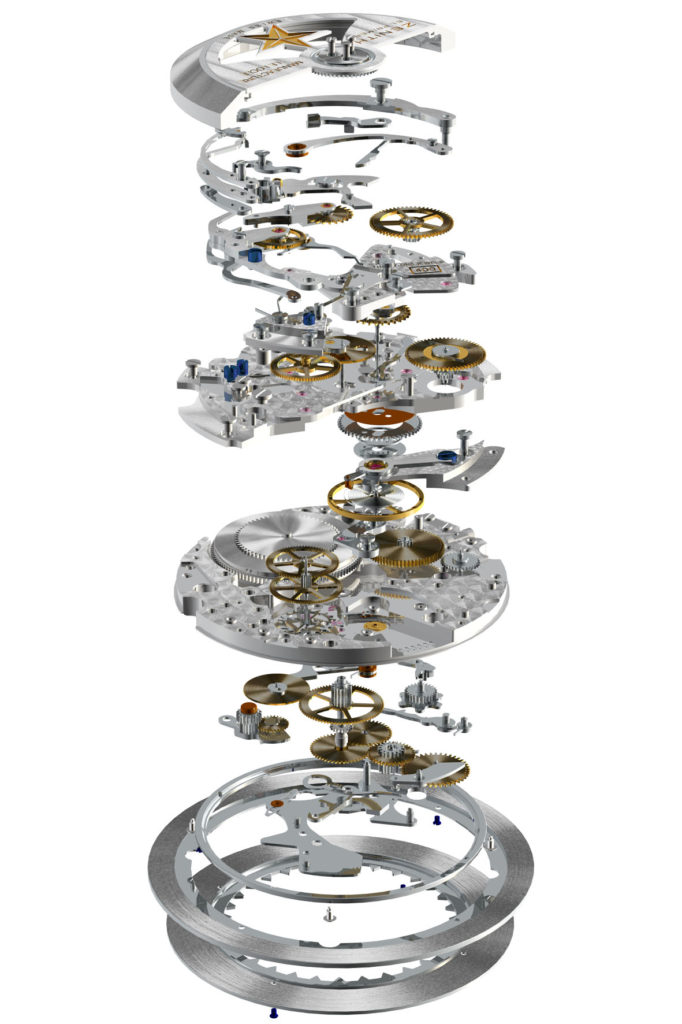

The chronographic function was to be integrated within the caliber and operated by a column wheel, rather than being added to a three-hands module. Then, the frequency should have been so high as to allow the measurement of the tenth of a second. Finally, there was the date. All within small dimensions. All these challenges led Zenith to exceed the schedule of four years.

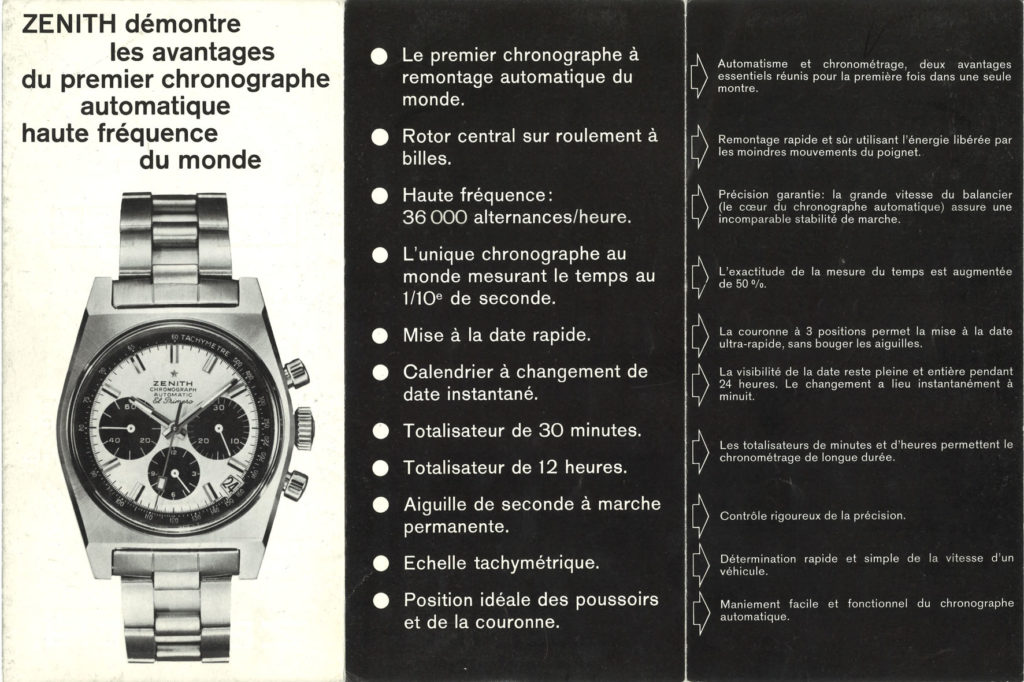

The announcement was made on January 10, 1969, anticipating the presentation scheduled for the following April in Basel. In fact, there were rumors that the other Swiss team involved in the design of the automatic chronograph – Breitling, Hamilton-Büren, Heuer, Dubois-Depraz – would have presented it before the Basel fair.

The announcement: “The Zenith and Movado watch companies have achieved an extraordinary feat in combining two precision watches in one. It comprises a high-frequency automatic watch with calendar along with a timer-chronograph allowing time measurements to the tenth of a second. It is equipped with an hour and minute timer. This is the first watch of its type in the world. The extraordinary feature is that both these mechanisms fit in a space smaller than that of a traditional chronograph. This model has all the advantages of a standard watch plus the date, automatic winding and the chronograph with timers and calendar.”

THE TECHNICAL CHALLENGES

If the caliber got famous for the 36,000 vibrations/hour, its main feature is the column wheel – which is not a real column wheel – chosen instead of the cam to engage and disengage the chronograph functions.

The normal wheel has a toothed wheel spool with saw teeth at its base; small trapezoidal columns on it move the levers, activating the chronograph functions with a rotary movement. The El Primero column wheel instead has a spoke wheel on the basis of the spool, without the trapezoidal columns. Despite the difference, it also activates the chronograph functions through rotation and not with the angular and lateral movement of the cam chronograph.

The high-frequency chronograph mechanism was assembled in a new automatic caliber; the winding system of this caliber had a high-inertia rotor, made by weighting the peripheral rotor through the insert of an outer segment of tungsten carbide (high-density material) and creating a central part with apertures which, in case of a violent impact, acted as a shock absorber. The rotor was mounted on six ball bearings and was bi-directional, so as to be sensitive to even the slightest movements of the arm.

A concentrate of innovation in terms of research and materials, to which Zenith has remained faithful, choosing not to return, as far as possible, to less extreme vibrations. The brand made El Primero and the 36,000 two flagships in the name of quality and brand identity.

HI-BEAT – SEIKO’S RESPONSE

Around the same years, 10,000 kilometers further east, Seiko’s workshops were looking for the same high-frequency performance. As early as 1960, the first Grand-Seiko-certified chronometer according to the brand’s internal standards, well above those established by the COSC, had already debuted in Tokyo. A few years later the chronometer indication was removed from the dial, thus declaring that the Grand Seiko were playing in a separate league.

While the chronometer designation may have been Grand Seiko’s initial goal, Japanese watchmakers wanted to push the limits of the challenge on the momentum of the watch’s success.

Back then, a frequency of 18,000 vibrations was the standard average; advances in improved hairspring tension, and the development of effective materials and lubricants also prompted Seiko to explore the high-frequency terrain for greater accuracy. So, the research on what would become the brand’s workhorse, the 36,000-vibrations Hi-Beat movement, began.

It was in 1967 that Seiko introduced its first Hi-Beat: the hand-wound 5740C. However, it was not encased in a Grand Seiko: it was the Lord Marvel who carried the first high-frequency caliber watch of the company.

A year later, it was the turn of Grand Seiko’s Hi-Beat, the 61GS, developed from a Seikomatic 5 base and powered by a 36,000-vibration Hi-Beat 6145 automatic caliber. Even today, the 61GS is considered as one of the brand’s best creations, and the 6145 arguably the best automatic movement ever made by Seiko.

Perhaps, however, not everyone knows that a curious internal rivalry within Seiko also led to the birth of Hi-Beat. As early as the 1960s, King Seiko (KS), a sub-brand of the company’s elite lines, aimed to dethrone Grand Seiko as the company’s top-of-the-line brand.

The very first King Seiko model was produced in 1963 by Daini Seikosha Co., as a response to Suwa Seikosha Co.’s 1960 release of the Grand Seiko. It was inevitable that both brands were aiming for a Hi-Beat watch.

The first generation of King Seiko was a hand-wound, unnumbered 25-jewel caliber. Later, the 18,000-vibration hand-wound King Seiko caliber 44 models were released, paving the way for the brand to follow in the footsteps of Lord Marvel and Grand Seiko and come at its own high-frequency movement.

The result was the King Seiko 45 series, with a hand-wound movement beating at 36,000 vibrations/hour: the brand’s first Hi-Beat. Its accuracy was so unreal for that period of time that Seiko labeled it at the Class A standard, the ultimate in accuracy.

Both King Seiko and Grand Seiko developed their Hi-Beat calibers until they were overwhelmed by the quartz crisis. The fact that King Seiko never came back while Grand Seiko was reborn in the late 1990s is for some the certification of the latter’s ultimate supremacy. In any case, their rivalry has contributed to Japanese excellence in high-frequency calibers, not inferior to that of Switzerland.

THE OTHERS

Of course, Zenith, Seiko, Girard-Perregaux and Longines are not the only brands which dealt with high-frequency calibers. Just to name a few, the Ulysse Nardin San Marco or the 36,000-vibration Zodiac SST, or the 72,000-vibration Breguet Classique Chronométrie 7727.

TAG Heuer has created a chronograph that beats at 360,000 vibrations/hour, the Mikrograph, and one even at 7,200,000, the Mikrogirder, in which the regulating organ for the chronograph is a tuning fork. Technical virtuosity, whose usefulness is to be demonstrated. The real challenge, those of the 36,000 vibrations, had already been fought (and won) for some time.

By Davide Passoni